1. The “Too Perfect” Patina

A real antique should show some signs of age—tiny scratches, uneven wear, or a bit of oxidation. But scammers often use chemicals or heat to create a fake patina that looks centuries old. The trick works because the surface looks aged without the fragility of a true antique. If something looks both ancient and flawless, that’s usually your red flag.

The reason this scam fools even seasoned buyers is that patina can be hard to authenticate without lab testing. Dealers may even point to the color or texture as proof of authenticity. Unfortunately, many modern fakes use high-quality distressing techniques that mimic natural oxidation. Always check the wear patterns in hidden spots, like undersides or screw holes—fakes often skip those.

2. Reproduction Furniture Sold as Original

Reproductions can look stunning—and sometimes they’re even made with period-accurate materials. But the problem starts when a dealer “forgets” to mention that the piece was built last decade, not last century. Modern reproductions often use old wood or reclaimed nails to boost the illusion. Buyers get tricked because the craftsmanship feels right, even if the timeline doesn’t.

The best clue is the construction. True antiques often have hand-cut dovetails, irregular nails, or uneven joinery, while machine precision gives away newer pieces. Even the scent of the wood can help—older furniture tends to have a distinct mustiness that’s tough to fake. When in doubt, bring a UV flashlight; newer glues and finishes fluoresce differently from old varnish.

3. “Restored” Pieces That Are Mostly New

Restoration is normal in the antique world—but when 80% of a “restored” item is new material, it’s basically a replica. Unscrupulous sellers might only keep one original drawer front or knob and rebuild the rest. To the untrained eye, it still looks like a complete antique. The problem is you’re paying full antique prices for something that’s mostly modern.

Experts recommend asking for documentation of the restoration process. Honest restorers will note which components were replaced and why. If the seller gets defensive or vague, that’s a bad sign. A real antique with minimal restoration will have inconsistencies and minor flaws that reflect its history, not a pristine showroom finish.

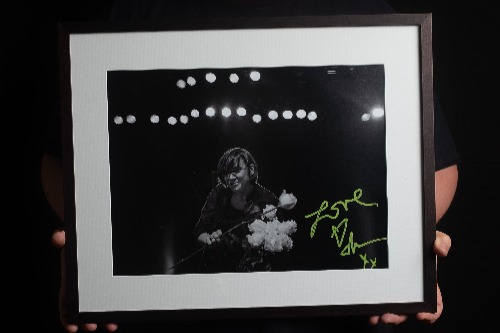

4. Forged Signatures and Labels

A common scam involves faking a maker’s mark or signature to increase value. Fraudsters use engraving tools, stamps, or even digital transfers to imitate authentic labels. Because famous cabinetmakers or artists can add thousands to a price tag, this trick is tempting. Many buyers get caught because the signature looks perfectly aged.

Authentic marks often have slight irregularities—uneven lettering, fading ink, or inconsistent placement. Fakes tend to be too crisp or located in the wrong spot. Comparing multiple verified examples of a maker’s mark can reveal inconsistencies fast. If the label looks “too clean,” that’s usually your cue to question it.

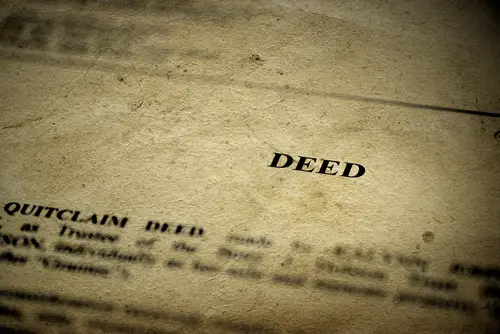

5. Misrepresented Provenance Papers

A piece with a glamorous backstory—“from a French chateau” or “owned by a Victorian duchess”—sells faster. Scammers exploit that by forging provenance documents, often complete with fake letterheads and signatures. These papers look official but rarely hold up under scrutiny. Smart buyers get duped because the story feels so convincing.

To protect yourself, cross-check the details. Real provenance often ties to verifiable records like auction listings, estate inventories, or museum references. Fake documents tend to include vague locations and unverifiable names. If the paperwork looks freshly printed or uses modern fonts, it’s probably not authentic.

6. Overpolished Silver

Silverware and serving pieces that shine like mirrors may seem valuable—but they might actually be stripped of their antique charm. Overpolishing removes patina, which collectors value for its authenticity. Scammers do this to make an item look newer and hide flaws or repairs. Ironically, it often lowers the piece’s true value.

Real antique silver has a softer luster and subtle darkening in crevices. If every groove gleams, it’s probably been tampered with. Overpolished silver can even lose its hallmarks, making it harder to date. When buying, look for those natural dark accents—they’re signs of a well-aged piece, not neglect.

7. Franken-Antiques

Sometimes dealers merge parts from different items to create something “rare.” For instance, a chair with 18th-century legs and a 20th-century seat gets marketed as an “original Georgian.” These Frankenstein creations are tricky because the old components lend legitimacy. Buyers think they’re getting one-of-a-kind craftsmanship—when really, they’re getting a mash-up.

You can spot them by looking for mismatched wood grain, inconsistent tool marks, or varying oxidation between parts. Screws and nails that don’t match are another giveaway. If a piece looks stylistically inconsistent, that’s worth questioning. True period pieces usually have harmony in design and wear throughout.

8. Artificial Craquelure in Paintings

Old oil paintings develop a web of fine cracks called craquelure. Forgeries often fake this texture using heat, chemicals, or intentional cracking mediums. It’s convincing at a glance but usually too uniform or exaggerated. Many buyers fall for it because genuine craquelure is seen as proof of age.

To test, gently inspect the cracks under magnification. Real craquelure follows the brushstrokes and varies in depth. Fakes may have cracks that cut across the image unnaturally. Also, synthetic cracking tends to flake differently under UV light—another clue for careful collectors.

9. Repatinated Bronze

Bronze sculptures and hardware darken over time, forming a natural patina. Scammers sometimes use acids to speed that process, creating a deep, “antique” finish in hours. Because true patina takes decades, it’s valuable—but the fake version can fool even experts. The artificially dark color can hide casting seams or modern welds.

The best approach is to study texture. Authentic patina has gradual color shifts and uneven buildup, while fake versions are often too uniform. Check the undersides or hidden areas—if they’re bright and clean, that’s a red flag. Natural patina penetrates deeper and doesn’t rub off easily when touched.

10. Recast Bronze Statues

Many antique bronze statues have been recast using modern molds from originals. These copies retain the same shape but lack the fine detail of early casts. Unscrupulous sellers present them as authentic 19th-century works. The weight and color might match, so even experienced buyers can slip up.

To spot a recast, look for softened edges, missing signatures, or mold marks not present in originals. Recasts often use different alloys, resulting in a duller tone. Checking provenance and comparing known casts from museums can reveal discrepancies. A missing foundry mark is another strong clue.

11. Fake Oriental Rugs

Hand-knotted antique rugs are a collector’s dream—and an easy target for fraud. Some dealers sell machine-made rugs as “handwoven,” or artificially age them using tea stains and abrasion. The wear looks realistic, but the rug’s construction tells the truth. Buyers often get fooled by the charm of the design and the smell of “old” fabric.

Flip the rug over and check the knots. Hand-knotted rugs have irregular patterns and visible weft threads. Machine-made versions look too uniform. A genuine antique rug should also have uneven fading consistent with use—not just random patches of discoloration.

12. Faux Ivory Carvings

Because real ivory is heavily restricted, fakes made from resin or bone powder are everywhere. Scammers claim these are “pre-ban ivory” or “estate pieces” to skirt regulations. They’ll even add fine lines to mimic ivory’s cross-hatching pattern, known as Schreger lines. The replicas feel convincing, but their value is nowhere near authentic ivory’s.

To tell the difference, inspect the material under light—real ivory has intersecting lines, while resin looks smooth and glassy. A hot pin test can reveal synthetic materials (though not recommended on valuable pieces). Ethical buyers should also be wary of any vague claims about age or legality. If provenance feels sketchy, walk away.

13. Antique Clocks with Modern Movements

Dealers sometimes install new clock mechanisms inside old cases, calling them “fully functional originals.” The clock looks antique, but its heart is modern. That repair might seem harmless, but it destroys authenticity and collector value. Buyers often miss it because they’re thrilled the clock actually runs.

To check, open the back and examine the mechanism. Genuine antique movements have hand-engraved marks, uneven screws, and aged brass. Modern replacements are shiny and machine-made. A truly valuable antique clock is expected to tick imperfectly—that’s part of its charm.

14. Misdated Ceramics

Changing a date mark or misinterpreting a pottery hallmark is a classic scam. A 1930s reproduction can suddenly become an “18th-century treasure” with a little clever aging. Fraudsters might file down areas or repaint marks to confuse buyers. Because ceramics are durable, it’s hard to tell old from older.

Experts recommend studying glaze and clay composition. Antique glazes often show fine crazing and depth, while newer ones appear uniform. The foot ring—the unglazed bottom edge—also tells a story; true antiques show natural wear there. If it looks freshly sanded or oddly clean, something’s off.

15. Auction House “Estimates” as Authenticity

Not all auction listings guarantee authenticity, but some buyers assume they do. Shady sellers use phrases like “attributed to” or “in the style of” to avoid outright lying. These terms sound authoritative but really mean “we’re not sure.” Even educated collectors sometimes overlook those subtle disclaimers.

Always read auction descriptions carefully. “Attributed to” suggests possible authorship, not confirmation. Real authentication requires expert evaluation and provenance. When in doubt, consult a specialist before raising that paddle—confidence alone isn’t proof of age.

This post 15 Antique Scams That Even Smart Buyers Fall For was first published on Greenhouse Black.